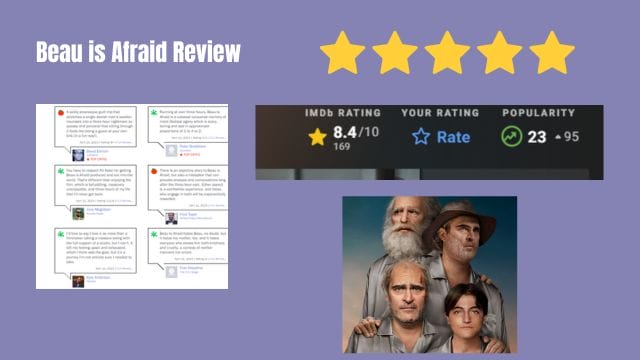

Beau is Afraid Review: Poor Beau has spent nearly half a century on Earth, but he has never truly lived. What has Beau done with his life since his birth, which director Ari Aster depicts from Beau’s perspective at the beginning of his wildly self-indulgent and frequently surreal third film, “Beau Is Afraid,” lingering long enough to see the umbilical cord is cut?

Can it be said that he ever truly developed a separate identity from his successful single mother, Mona Wasserman, who haunts the film for three hours before unveiling herself?

Not since “Psycho” has an absent mother hovered so large over a film’s protagonist, here portrayed by Joaquin Phoenix (check out how much money does Joaquin Phoenix have?), as he cowers from the world. This deranged road trip follows Beau across the country — and through several substitute families — in order to confront his intimidating Jewish mother.

Read our related articles:-

The cult director pokes fun at a hapless man-child crippled by guilt, shame, and innumerable other superstition while maintaining his signature slow-building sense of dread.

In addition to agoraphobia and arachnophobia, he has a genetic condition (swollen testicles, almost subliminal here, but soon to saturate the internet with animated GIFs) that has kept him a virgin for all these years.

“Bardo” began with a newborn so repulsed by the outside world that obstetricians actually forced him back into the womb, so it’s kind of a pity that Iárritu beat him to it.

Read More –

- Love Victor Season 3 Reviews: Finding Courage and Acceptance!

- GAP Episode 8 Release Date, Plot, Cast, Trailer, Rating, Reviews and More!

This sight joke would have better suited Beau. Instead, after depicting Beau’s birth, Aster fast-forwards four decades to discover the mama’s boy in psychoanalysis, where character actor Stephen McKinley Henderson is as approachable a therapist as one could hope to confide in.

Beau has great difficulty controlling his anxiety, which is comprehensible given that Aster depicts his terrifying inner-city neighbourhood as a hellscape reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch, as Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson might have filmed it: Everyone appears dangerous, from the children with firearms to the face-tattooed pervert who pursues Beau to his home.

The simple act of crossing the street becomes an almost superhuman challenge, and in the time it takes Beau to accomplish this, all the oddities he was trying to avoid outside march up to his apartment like zombies and proceed to destroy it.

Had the day gone according to plan, Beau would be flying to Florida to visit his mother. On the other end of the phone, we hear the legendary Broadway actress Patti LuPone (you can follow her on Instagram). But Beau has a habit of sabotaging himself, which becomes a running gag in a film that inflicts the trials of Job on a character who begins in a much less secure position.

Beau has neither children nor wealth, so his misfortunes more closely resemble the caprices of a cruel deity in this case, the director punishing his creation for our amusement.

There is no denying the influence of Charlie Kaufman on Aster’s worldview, which is combined with the navel-gazing cynicism of underground comic artists.

Longtime admirers, however, will recognize the same enduring obsessions that Aster has been exploring since his AFI thesis film, “The Strange Thing About the Johnsons,” a transgressive, incestuous quasi-“Cosby” parody.